Rice and Water

The ingredients of sake are rice and water. Sake is made from just these two elements.

Rice and water have long been central to Japanese life, providing daily nourishment and serving as essential elements in prayer and purification. They have supported both living and calming one’s heart.

Water purifies the body and prepares a space. Rice sustains life and symbolizes gratitude. Together, they are quietly rooted, deep at the core of Japanese values.

Sake Brewing Begins with Rice Farming

Water flows from the mountains to the rivers and into Lake Biwa. Agriculture in Shiga Prefecture has long depended on this cycle. After the war, however, inflows of domestic and agricultural wastewater led to serious pollution of Lake Biwa, prompting prefecture-wide awareness of the need to protect the lake. In 2001, Shiga Prefecture established a certification system for eco-friendly agricultural products to promote environmentally-conscious farming. As a result, Shiga now leads Japan in implementing the national government’s initiatives targeting environmental conservation in agriculture.

Located at the northernmost tip of Lake Biwa — the Kinki region’s water reservoir — our home is the home of headwaters. Precisely because of this, we believe it is our responsibility to farm with minimal impact on the environment, to preserve the beautiful, clean water. The five farmers we partner with all cultivate rice in the Kohoku region. They share a deep respect for nature and a passion for rice farming that exceeds even the prefecture’s environmental standards. Working alongside such dedicated farmers engaged in rice cultivation — the very first stage of sake brewing — is one of Shichihonyari’s greatest strengths.

At the age of 23, Yagura returned from Osaka to begin as the fifth-generation farmer in his family. After pursuing pesticide-free cultivation, he advanced further into natural farming. Guided by the philosophy that delicious rice is healthy rice, he avoids pesticides and chemical fertilizers, letting the rice grow without stress, drawing on the soil’s inherent strength and microbial activity. He has also established a community hub called ridō (里道), actively fostering exchanges aimed at preserving the rural landscape for future generations.

(partner since 2010)

“You have to grow rice that makes people happy.” Inspired by her grandfather, who practiced organic farming at a time when pesticide- and chemical-based agriculture was the norm, Tanaka began farming part-time in 2017 and later transitioned to full-time farming. She uses only mountain water and groundwater from the region for her rice cultivation, and reuses sake lees from our brewery as fertilizer—striving for a cycle of local resources. At the same time, she actively adopts new methods and technologies, such as robotic weeders.

(partner since 2020)

After working in the food industry, Shimizu began farming in 2003. Drawing on his experience in food production, he actively promotes sixth-industry work — the concept of integrating primary, secondary and tertiary industries. Specifically, he handles rice production, processing, and sales under the guiding principle of “food safe for children to eat.” His developments include creative rice-based products such as ready-to-eat multigrain rice and a wide variety of flavored puffed-rice snacks. Always sharing new possibilities for rice and expanding its potential, he also engages in sake rice cultivation.

(partner since 2011)

After working for companies in Nagoya and Osaka, Tatemi returned home in 2002 to take over the family business. While minimizing the use of pesticides and chemical fertilizers, he views farmers not merely as producers, but as connectors between people, food, and the land. He participates in initiatives with chefs, such as the Grow Rice Project, aimed at increasing rice self-sufficiency. He organizes Shichihonyari’s annual cedar ball (sugidama) making, bringing together a wide range of participants. Through his approachable character, embodying direct producer-consumer connections, many feel deeply drawn to this region.

(partner since 2011)

After returning from training at a large-scale agricultural corporation in Ishikawa Prefecture in 2015, Morikawa embraced the words of his predecessors: “Leave nature intact as an ecosystem, and learn how to respectfully receive what it offers.” He practices farming with minimal pesticide use and produces JAS-certified organic rice. He also promotes labor-saving smart agricultural machinery and the consolidation of farmland into larger plots. Despite the large scale of his operations, he is widely respected for his meticulous field management.

(partner since 2001)

Shichihonyari’s Sake Rice

Rice from this region, called Omi-mai, has an excellent and long-standing reputation for supporting the imperial capital of Kyoto. Shiga Prefecture rice is acclaimed for its consistent quality and reliable supply. In the past, Shiga-grown Nihonbare rice was used nationwide as a benchmark variety for evaluating flavor and quality. Though a type of table rice, it was also suitable for sake brewing and widely used by breweries across Japan. The stability and trust cultivated by Shiga-grown rice continue to sustain sake brewing at Tomita Sake Brewery today.

A historic sake rice variety from Shiga Prefecture. Its grains are large, with a relatively low shinpaku occurrence rate — a measure that refers to the percentage of grains in a sample with a visible starchy core. The grains are very hard and well-defined, producing sake with a crisp finish. Its distinctive depth of flavor is said to be well-suited for aging. Tamasakae is unique yet understated, aligning closely with Shichihonyari’s philosophy, and given its versatility of polishing ratios from 45% to 80%, it is the starting point for any of our new initiatives. It reveals its true character when paired with food. It is no understatement to say that Tamasakae is our brewery’s core variety.

The most widely cultivated sake rice in Japan. It has a deep connection with Shiga via its parent, Wataribune. Nearly a century after its development, it remains the highest-regarded sake rice and is widely grown in Shiga. While Shich Hon Yari uses it sparingly, among many distinctive rice varieties, it stands out for its exceptional ease of brewing.

Sake rice bred by crossing Shiga’s representative variety Tamasakae with Yamada Nishiki, often called the king of sake rice. It was developed to create a ginjo rice suited to Shiga’s environment. Though its thousand-grain weight is lower than Tamasakae’s, the individual grains are large like Yamada Nishiki, and exhibit a high shinpaku occurrence rate. In contrast to Tamasakae, it is simultaneously very soft and low in protein. The rice itself does not dominate, allowing the brewing approach to be clearly expressed. The Ginfubuki name is said to come from the starchy core pattern resembling swirling snowflakes.

A pure-line selection of Wataribune, the parent of Yamada Nishiki, this is a native Shiga variety. Despite being promoted by Shiga Prefecture from 1916 to 1959, it virtually vanished until recently, when it was revived as a Shiga original brand. Extremely soft and somewhat difficult to handle, it conveys a rustic, local character. At low polishing ratios, it shows strong individuality; at high polishing ratios, it becomes refined and elegant — revealing both its breadth and enduring potential.

A native Shiga variety once so widely cultivated that people talked about “Kamenoo in the East, Asahi in the West.” Records show it was commonly used at our brewery until the mid-20th century. After the war, it nearly disappeared due to the proliferation of newer varieties, but revival efforts by local producers are now underway. As a native variety well suited to Shiga’s climate and landscape, its growing popularity is thanks to its simplicity and its ability—both in sake and as food—to convey the pure, inherent flavor of rice.

Will This Water Sustain Us Forever?

Sake flavors are not shaped solely by rice. Rain and snow falling on the mountains beyond seep into the earth, passing ever so slowly through layers of soil and rock over long stretches of time. A record and memory of this land, the water eventually emerges as brewing water. As such, we believe the water itself is the taste of the land.

Rice can be cultivated by human hands. But water cannot be made by people. Once depleted or polluted, it cannot be restored. Though Japan is said to be rich in water, there is no guarantee that this land’s water will remain available forever.

That is why we take water so seriously. To understand water, we look to the mountains. We turn our eyes to the forests, the soil, and the cycle of this land. So that the water may continue to flow here. Our commitment to the future of water goes beyond sake brewing.

An Encounter 40 Years from Now

At Tomita Sake Brewery, we draw brewing water from an 18-meter-deep well on the brewery grounds. Dug anew in 1769, this well has been our water source for nearly 300 years.

When and where does this water come from?

Will we always be able to brew with it?

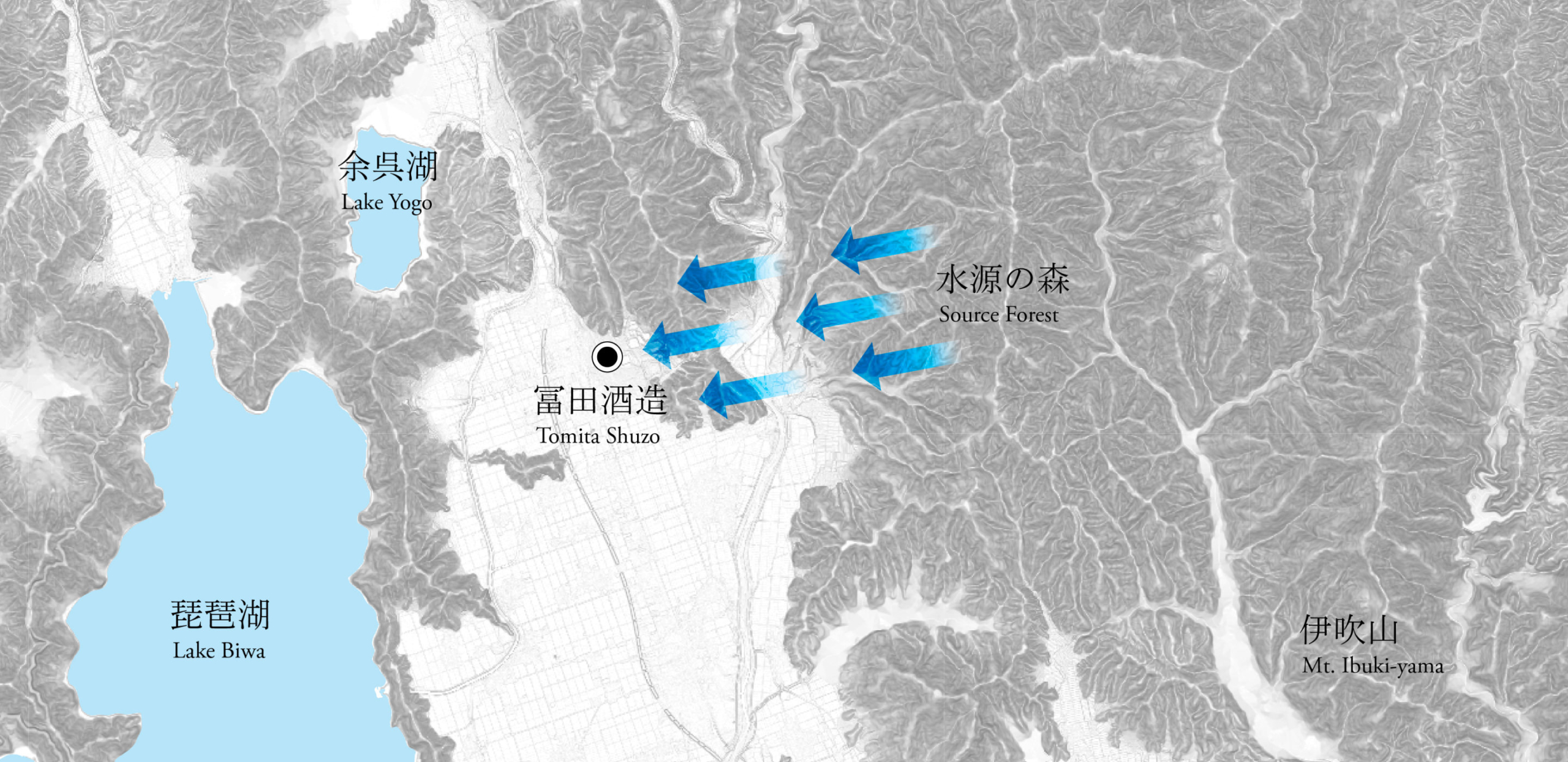

Joint research with a university revealed that the water we use today travels underground for 35 to 40 years before reaching the brewery. Its origin lies in rainfall and snowmelt from the mountains of the Ibuki range, including Mt. Kodakami to the brewery’s east. Long revered as a sacred site, Mt. Kodakami is brimming with water and known for its water-retaining beech forests and shrines associated with prayers for rain.

As the water permeates the earth’s layers, it absorbs trace minerals from the rock, emerging as clear, well-balanced, moderately soft water. After a 40-year journey, it encounters Shichihonyari’s “present”.

You can change the relative positions by dragging the image up, down, left, or right.

Visualizing the Path of the Water

Because the underground world is invisible to the eye, water easily fades from everyday awareness. We sought to preserve the unseen in visible form by visualizing groundwater flow through computer graphics created from scientific survey data.

Along what path did the water travel, and how long did it take to get here? When we understand the answers, water becomes more than a convenient natural resource; it manifests as an entity encompassing time and land.

Turn the tap, and water flows instantly. Yet even in these fast, convenient times, a single glass of water is the result of a journey far exceeding human perceptions of time. Knowing the path the water took subtly changes things, naturally influencing how we treat and think about water.

To visualize water is to visualize the passage of time on this land.

From mountains to villages, and on to Lake Biwa. With an ever-watchful eye on Shiga’s water cycle, we press on with our sake brewing, here, in this place.