1 | Founding

Tomita Brewery traces its origins to the early Tenmon period (1532–1555). The first-generation founder, Takayasu, is said to have moved to Kinomoto after turning to his mother’s family for help. He relinquished his warrior status and began brewing sake.

In Kinomoto, as early as 675 during the Asuka period, the Buddhist monk Soren founded Joshinji Temple (Kinomoto Jizoin). Revered by figures such as Kukai and Ashikaga Takauji, it became the spiritual center for surrounding temples. Owing to its strategic position connecting the Hokuriku region and the capital (Asuka, in present-day Nara), Kinomoto was formed as both a temple town and a post station. It was here, along the highway, that the Tomita family began operating their business. A 1563 travel record by a Daigoji Temple monk notes, “In Kinomoto, 16 mon were spent on sake and other items,” referring to the unit of currency at the time.

The Kohoku region of northeastern Shiga, where Kinomoto is located, is home to many ancient temples and the Mononobe burial mounds, connected to ancient Japan’s powerful Mononobe clan. About two kilometers east of the brewery stands Mt. Kodakami, long revered as a sacred site of mountain worship. During the Heian period (794-1185), the revival led by the monk Saicho resonated with the temples of the area. The unique Buddhist culture that flourished here later spread among the populace as devotion to Kannon, the Buddhist deity of compassion.

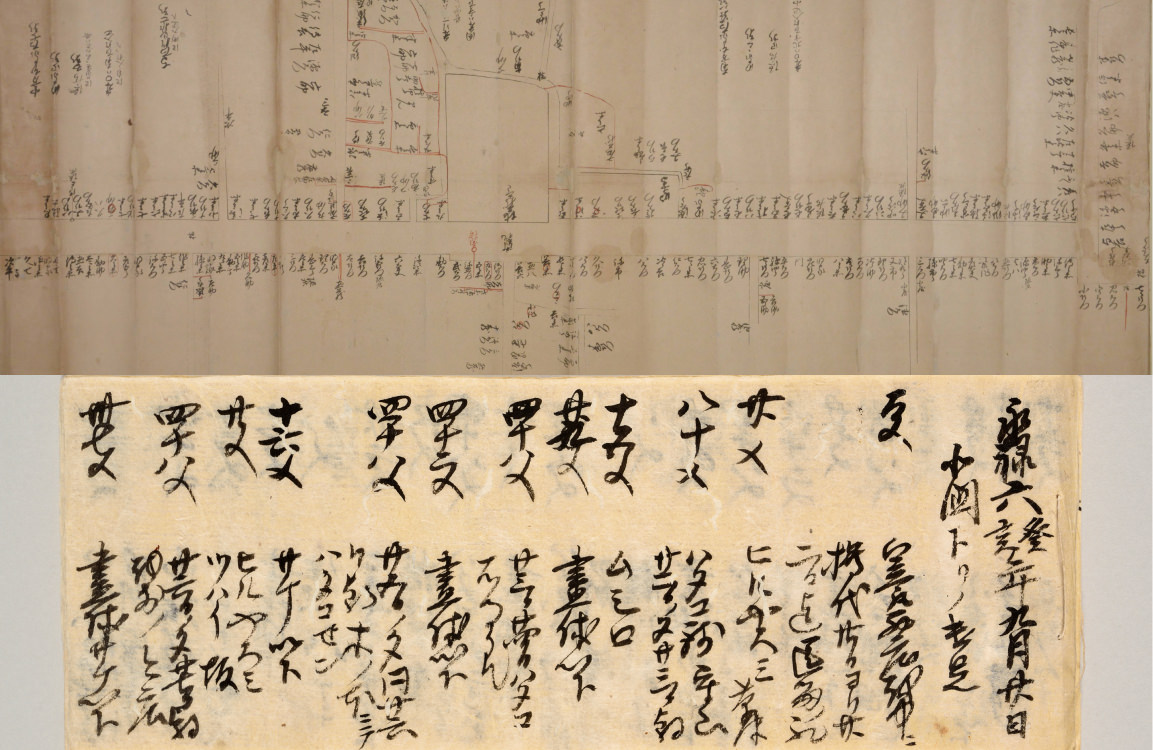

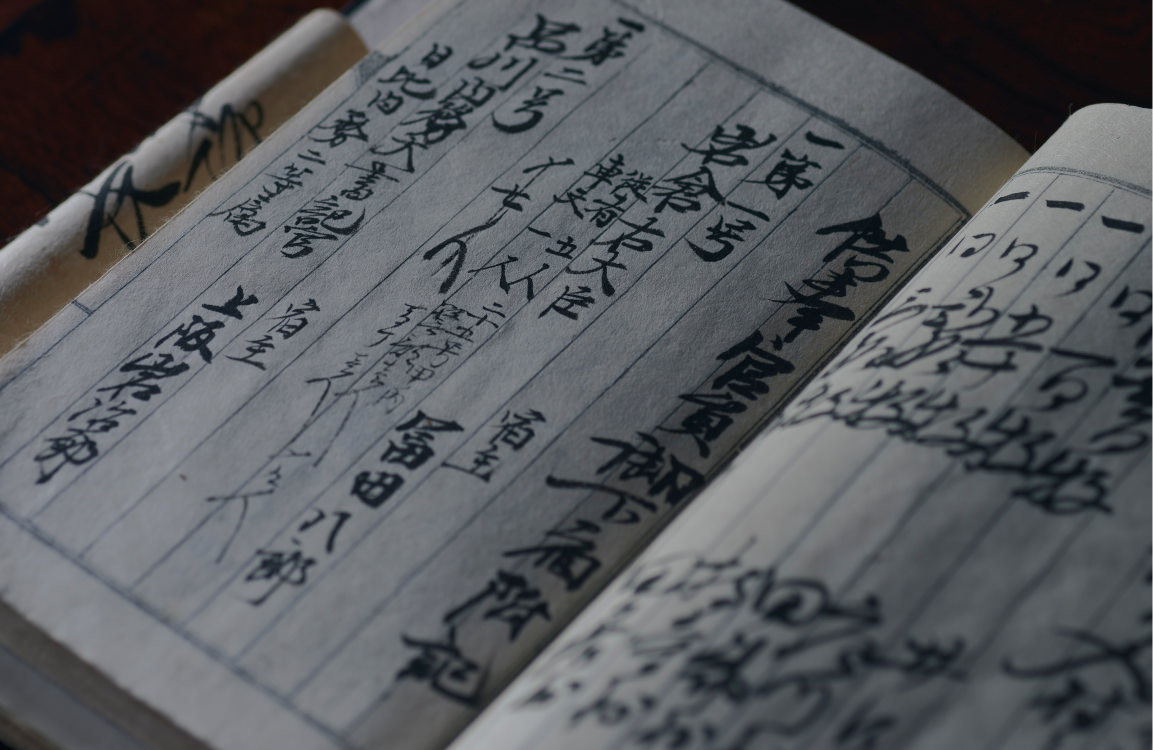

Lower — Record of people and goods dispatched to the Hokuriku region in 1563

2 | Warring States

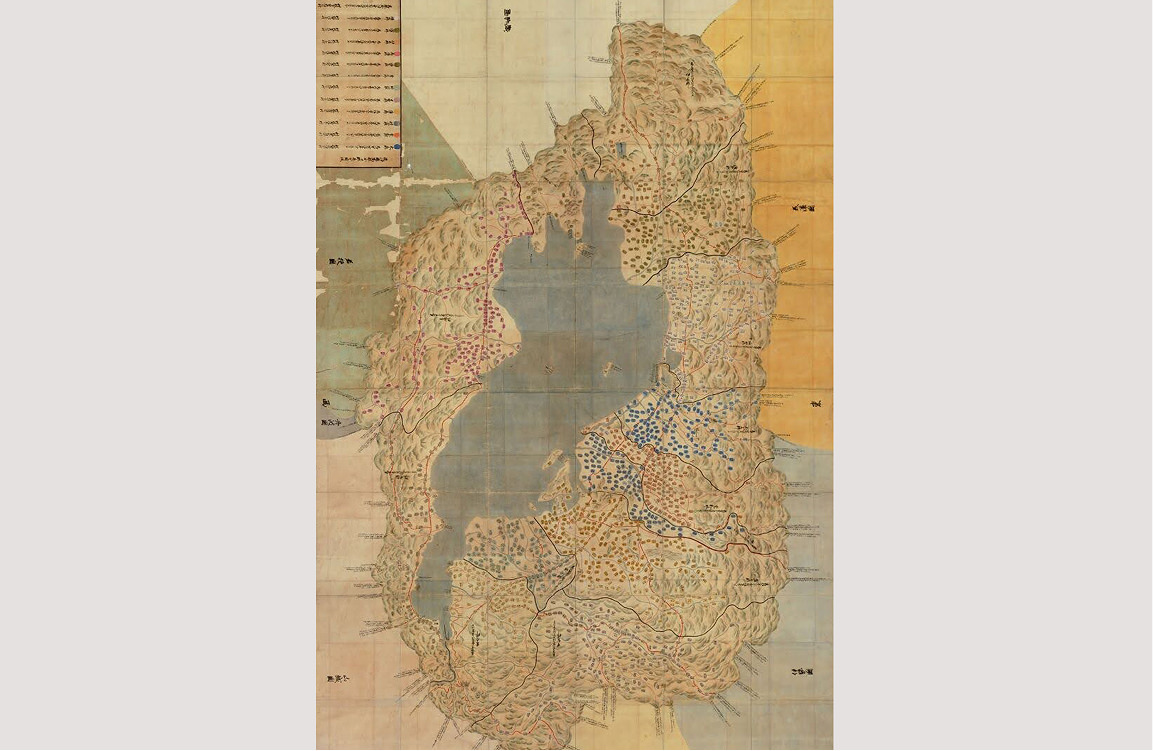

Due to its strategic importance, Kohoku was constantly at the center of power struggles during the Sengoku period (15th and 16th centuries). Fierce battles ensued after the region’s ruler, Azai Nagamasa, broke his alliance with Oda Nobunaga, including the Battle of Anegawa and the fall of Odani Castle, the Azai clan’s stronghold. During this time, Nobunaga ordered the burning of temples throughout Kohoku, and Joshinji was destroyed.

Following the Honnoji Incident and Oda Nobunaga’s death, Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Shibata Katsuie fought over Nobunaga’s succession in the Battle of Shizugatake (1583). Hideyoshi commanded his forces from Joshinji, and the young warriors who distinguished themselves in repelling Katsuie’s forces became known as the “Seven Spears of Shizugatake.” Katagiri Katsumoto later rebuilt Joshinji on the orders of Hideyoshi’s heir, Hideyori. The ornamental finials donated by Hideyori remain today.

3 | Early Edo

In 1657, the Tokugawa shogunate instituted the sake brewing licensing system, imposing limits by controlling rice allocations for sake production. There were approximately 27,000 sake breweries nationwide at the time. According to the 1696 Hikone Domain Sake Brewing Shares Registry, the Tomita family brewed 14 koku, equivalent to about 2,520 liters of sake.

Kinomoto prospered as a post town, a critical lodging point for daimyo traveling between Hokuriku and Edo on journeys between their home domains and Edo residences. Records from 1698 describe 119 households south of Joshinji and 74 to the north, along with the main inn reserved for daimyo and officials (now the Takeuchi residence), auxiliary inns, wholesalers, public lodgings, and more than ten merchant shops. The Tomita residence stood near Joshinji, directly across from the main inn. A canal once ran down the center of the street, lined with willow trees — a scene that endured until the early Showa period (1926-1989). According to records, the Maeda clan of Kaga Domain stayed at the main inn. Later, when Princess Yohime, daughter of the eleventh shogun Tokugawa Ienari, married into the Maeda family, she stayed in Kinomoto and bedding was prepared for 3,000 people.

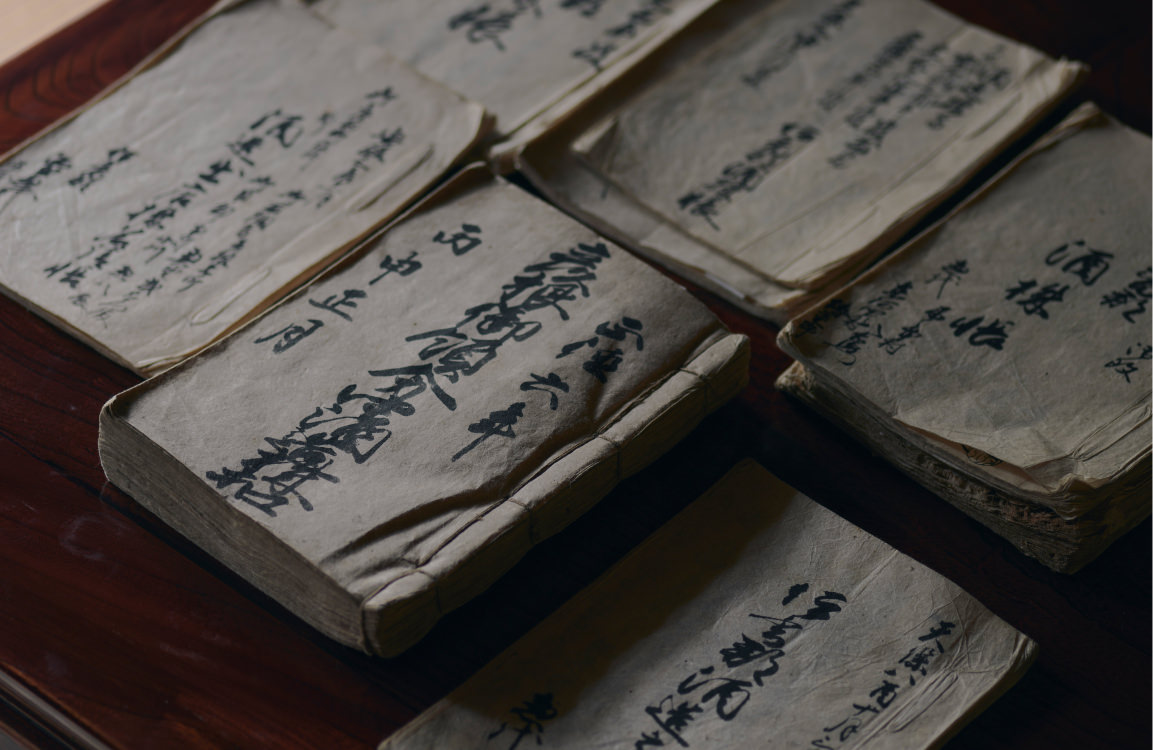

From the Brewery’s Collection

4 | Late Edo

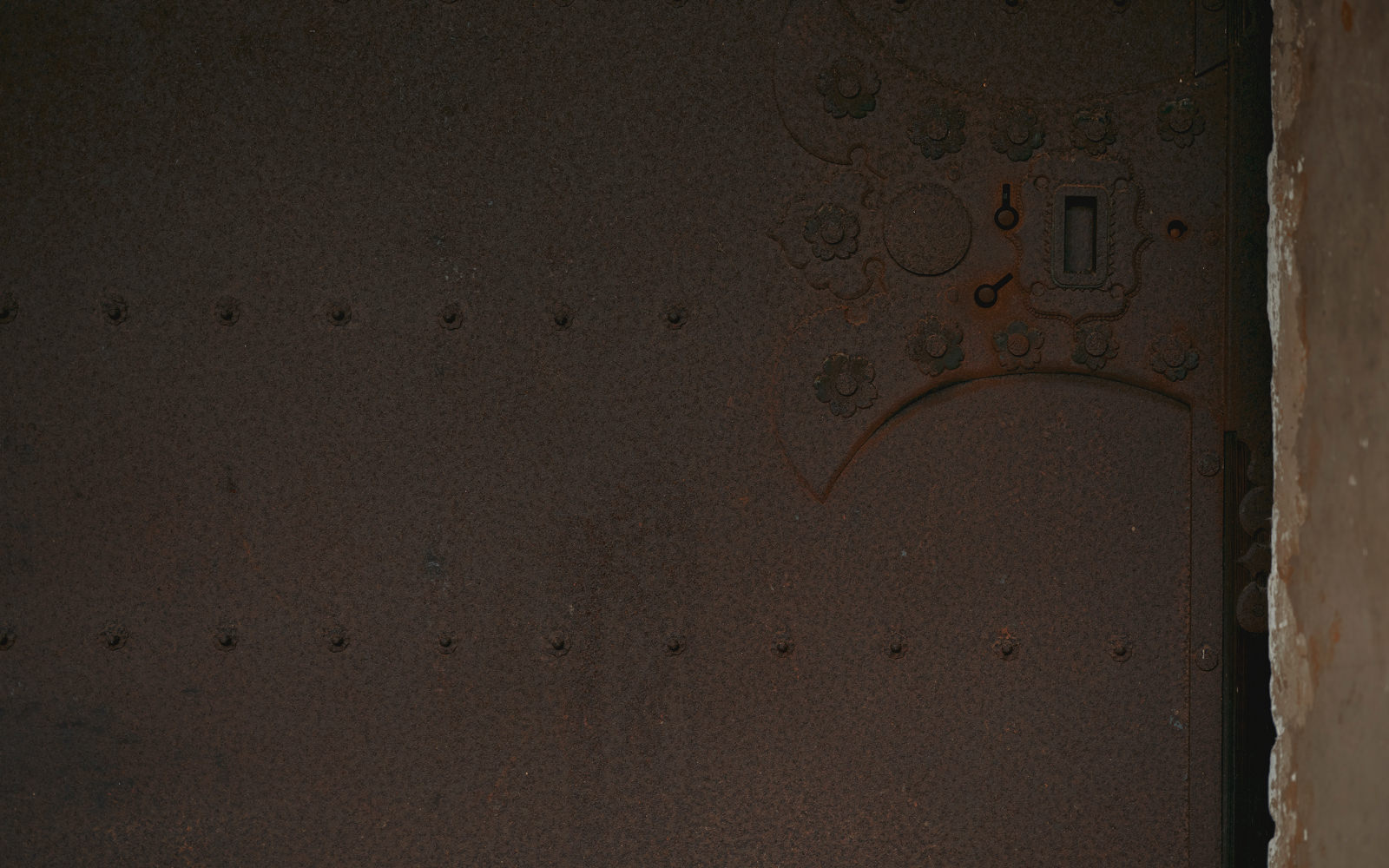

Kinomoto suffered two major fires in 1739 and 1744, both of which destroyed the Tomita residence. In 1744, the seventh-generation head, Churyo, relocated a building from Nishi-Goshu (present-day Takashima City) to rebuild the main house. This structure, now one of the oldest merchant townhouses in Kinomoto, was designated a Registered Tangible Cultural Property in 2019. In 1749, storehouses were newly built, and the well was dug anew in 1769. Water drawn from the well is still used in brewing today, and the brewery rebuilt in 1812 by the ninth-generation head, Chuji, continues to serve as the site of sake production. When repeated famines in the late Edo period strained the shogunate’s finances, nationwide sake production fell, with sharp declines in output likewise experienced by the Tomita family.

5 | Meiji

As Japan pursued modernization, the eleventh-generation head, Churi, played a central role in Kinomoto’s development. He first established an elementary school in 1871, before co-founding the Ikasokyusha social relief organization and the Kohoku Bank. Leveraging Kinomoto’s long tradition of sericulture, he also founded Kinomoto Silk Spinning, serving as its president and devoting himself to nurturing new industries.

In 1878, when Emperor Meiji toured the Hokuriku region and stayed at Joshinji, he was accompanied by Iwakura Tomomi, a leading figure in the Meiji Restoration, who lodged at the Tomita residence. The Kohoku Library, located near present-day JR Kinomoto Station, is among the oldest surviving private libraries in Japan. Opened in 1907, it originated from the Sugino Library, founded by a lawyer from neighboring Yogo for the community’s benefit. From the 12th-generation Hachiro to the 14th-generation Teruhiko, the heads of the Tomita family served as the library’s directors.

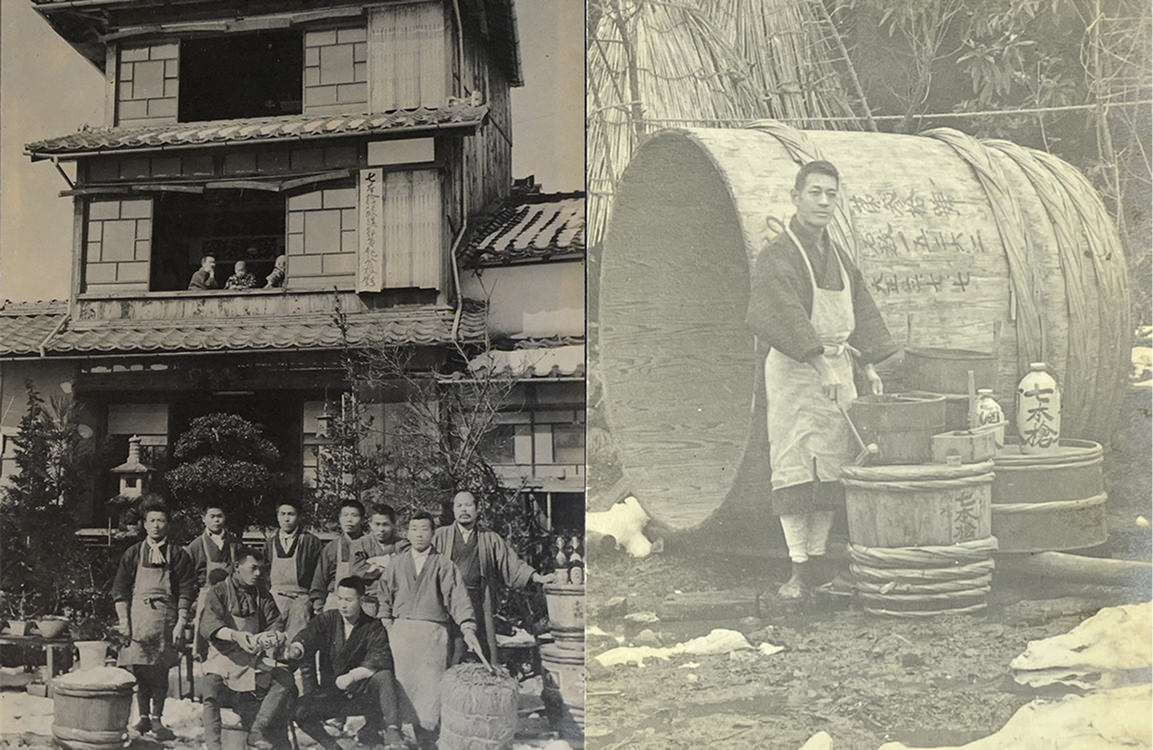

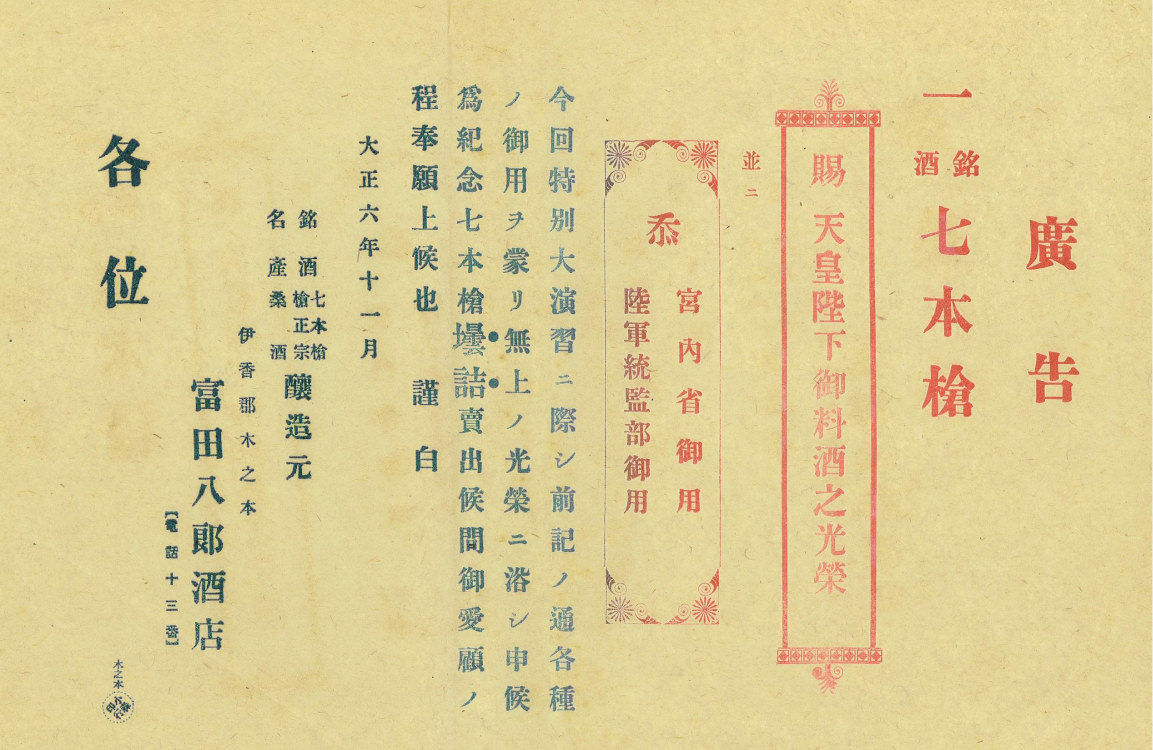

6 | Taisho

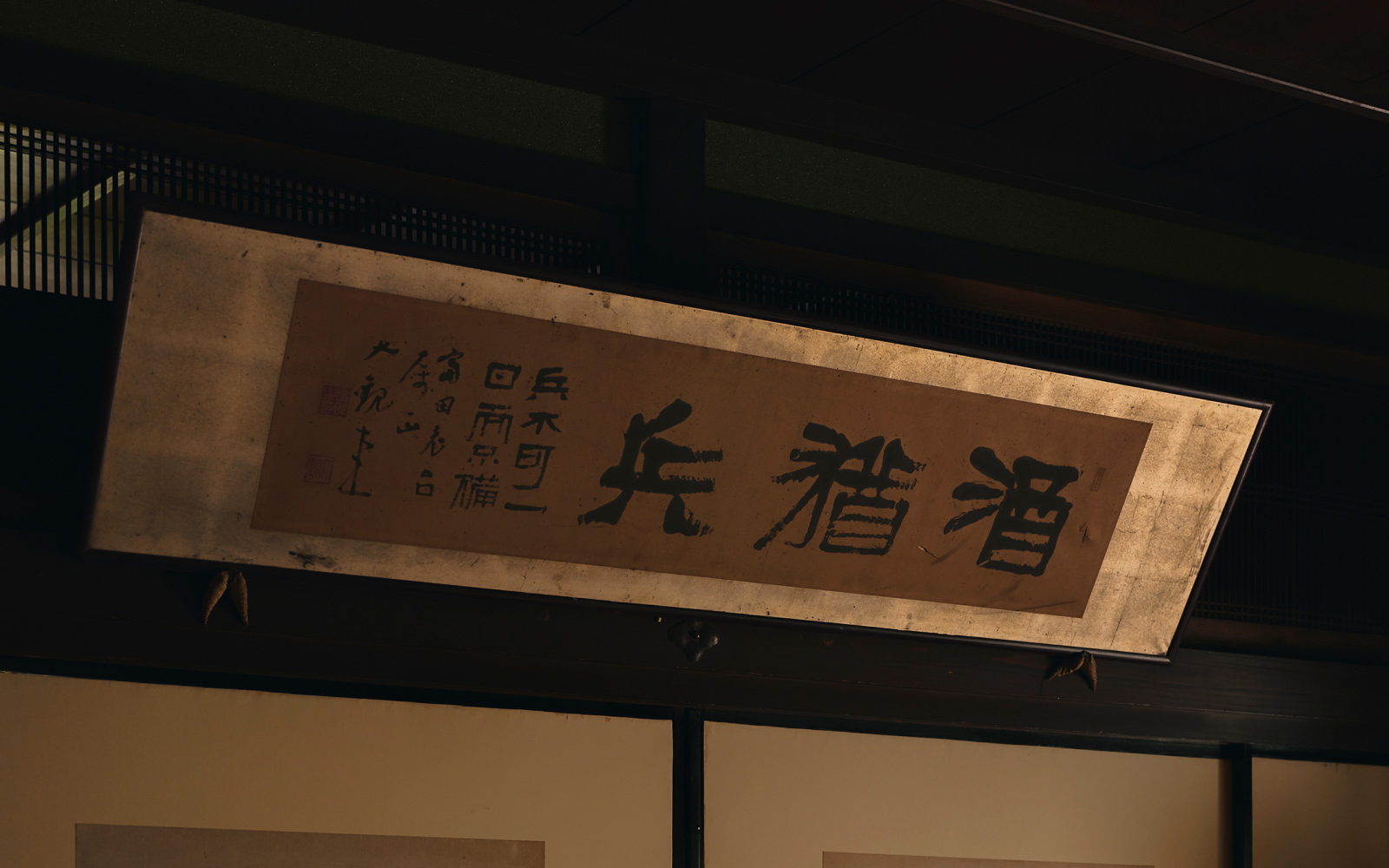

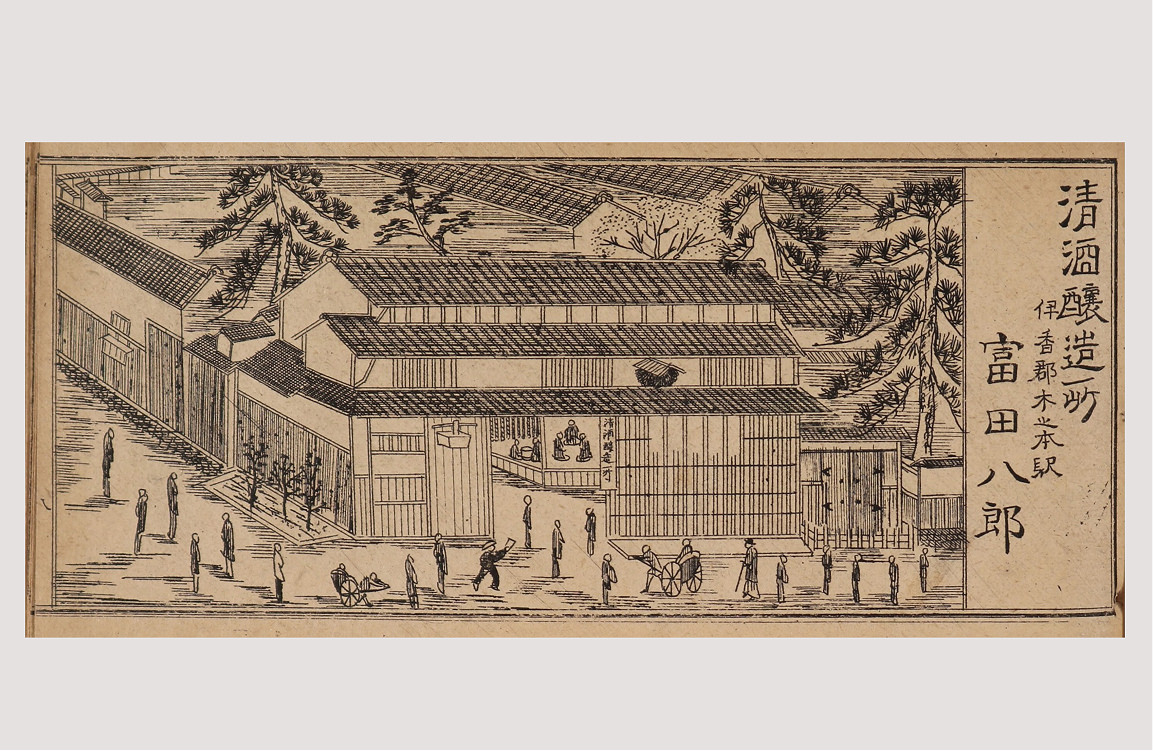

In the early 20th century, Hachiro devoted himself to brewing research, emulating renowned brewing regions outside the prefecture to improve quality, leading to frequent first-prize awards for Shichihonyari at sake competitions in Shiga Prefecture. The brand was later registered as a trademark, and Tomita Brewery was selected as an official supplier to the Imperial Household Department. Hachiro established a brewing research facility to raise the overall quality of sake in Shiga’s Ika District (home to Kinomoto), thereby enhancing the reputation of Ika Sake.

He was also a cultural figure. Through this connection, the artist Kitaoji Rosanjin stayed with the Tomita family, creating several works during that time. One of them is the seal carving for Shichihonyari still used on the label today. It was created when Rosanjin used the pseudonym Fukuda Taikan.

Right — Tomita Hachiro, 12th-generation owner

From the Brewery’s Collection

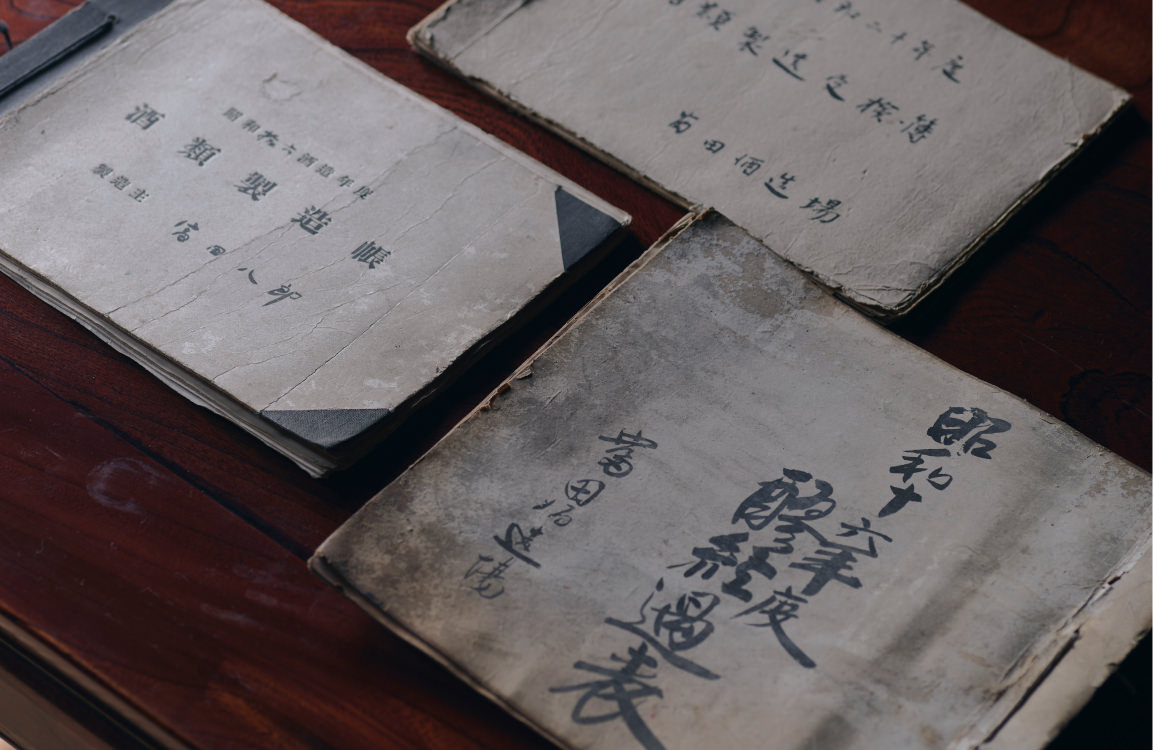

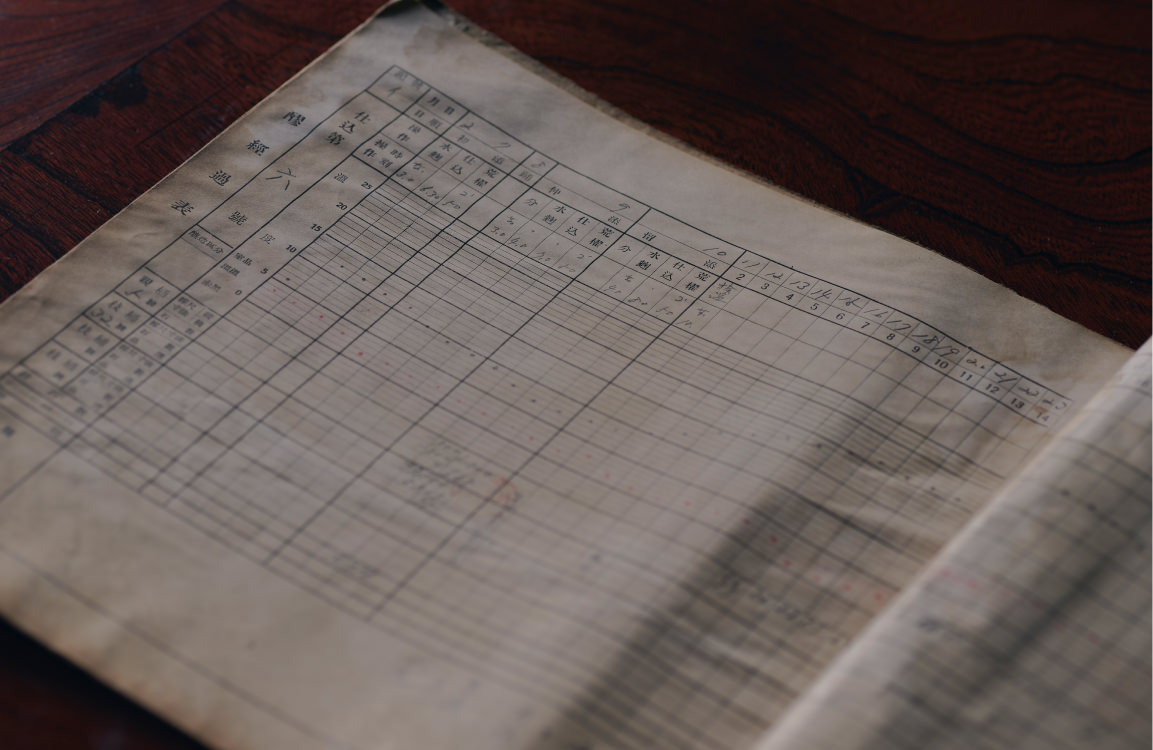

7 | Showa

For centuries, Kinomoto had hosted cattle and horse markets along the Hokkoku Highway. They flourished under domain protection during the Edo period but came to an end in the early Showa era. Today, iron rings for tethering horses remain in front of Tomita Brewery and several other residences along the road.

In 1935, the Kohoku Branch of the Agricultural Experiment Station was established to improve rice cultivation and agricultural techniques suited to the local climate. Around this time, the native rice variety Shiga Asahi gained prominence, replacing the main wet-land rice variety Shinriki. Brewing continued during World War II, with Shiga Asahi appearing in fermentation records in 1941. After the war, however, cultivation declined and the variety virtually disappeared.

In the latter part of the Showa period, Tomita Brewery was forced into temporary closure. This crisis was overcome by Kiyoko, mother of the current 15th-generation head, Yasunobu, who succeeded the brewery in the Heisei era (1989-2019).

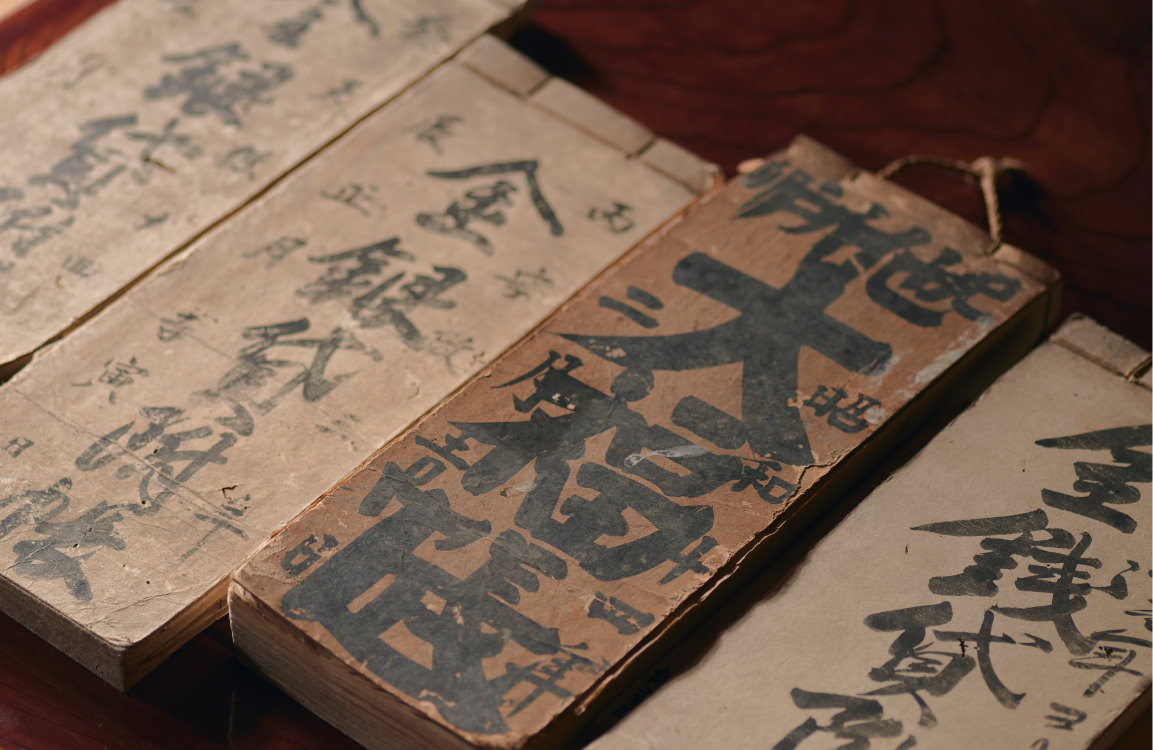

From the Brewery’s Collection

8 | Today

For many years, Tomita Brewery invited Noto master brewers to oversee production, while the brewery owners focused on management. In 2002, Yasunobu entered the brewery and transformed it into an “owner-brewer” operation, personally brewing sake while managing the business. He pursues sake brewing steeped in the land, with Kohoku’s climate, history, and culture refined into each drop of sake. The brewery’s initiatives include entrusting local farmers with the cultivation of sake rice, producing low-polish junmai sake, and brewing with chemical-free rice and revived native varieties.

In 2005, Tomita Brewery began overseas exports, sending its sake out to the world. In 2016, a new brewing facility was constructed according to traditional methods and using local timber and reclaimed materials from the brewery. This new space is the site of our aged sake storage, the revival of kimoto brewing, and the reclamation of wooden-vat fermentation. By incorporating traditional Japanese craftsmanship into both sake brewing and architecture, Tomita Brewery aims to preserve these practices for future generations.